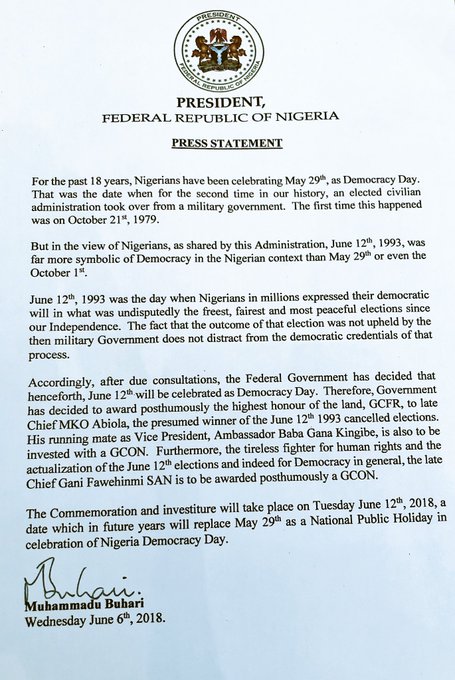

In a move that has been described both as manipulative and a masterstroke, President Muhammadu Buhari, a former military head of state, June 6, 2018 when he announced that the presumed winner of the June 12, 1993 presidential election, Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (MKO) Abiola, will be bestowed with the nation’s highest honour and June 12, that symbolic date, will henceforth replace May 29 as Nigeria’s Democracy Day.

The reactions have followed as expected, from those who were a part of the failed struggle for Abiola's mandate, to his children who waited for this day for more than two decades.

To the common man, the importance of this announcement would be lost on the common man, without the context of what happened in the weeks before and after June 12, 1993. If for nothing else, it will be remembered as a day when Nigeria's democracy, yet unborn, was smothered in its crib.

The misrule of Nigeria’s military era, from the 60s to the 90s, suppressed the collective choice of the people on two notable occasions, first with the January 1966 coup and Buhari’s time-out on Shagari’s agbada-wearing corruption on the last day of 1983.

But it was on June 12, 1993, that the people’s hopes was expressed in a nascent democracy; it would be murdered, along with a lot of the people who had fought to make it happen.

After Nigerians had tired of Babangida’s constant manoeuvring and corrupt dealings and had managed to pressure Maradona as he was then known, into agreeing to step down from his position, elections had been called for June 12, 1993.

The two candidates seemed to command enough of a followership to guarantee a tightly contested election.

Bashir Tofa was but it was Chief M.K.O Abiola, a wealthy international businessman and philanthropist who seemed to be the people’s favourite.

From 1972 until his death Moshood Abiola had been conferred with over a hundred traditional titles by numerous different communities in Nigeria, in response to his having provided financial assistance in the construction of secondary schools, mosques and churches, libraries, and 21 water projects in 24 states of Nigeria.

He was grand patron to 149 societies or associations in Nigeria.

In addition to his work in Nigeria, Moshood Kashimawo Abiola supported the Southern African Liberation movements from the 1970s, and sponsored the campaign to win reparations for slavery and colonialism in Africa and the diaspora.

All these fleshed out the image of a man who would fit seamlessly into the position of President of the world’s most populous black nation.

The voice of the People

The driving sentiment, support and scale of his campaign were collectively so overwhelming that when Nigerians went to the polls on June 12, 1993, it seemed the outcome was only a matter of protocol.

Elections in Nigeria, from the pre-colonial era, have always been marred or at the least, influenced by rigging and violence at various levels.

While it is difficult to make unnecessary assertions on the nature of the June 12 elections, not many in the country would have flattered themselves to expect a completely clean process.

Yet, international observers adjudged the June 12 elections to be the freest and fairest in Nigeria’s history.

There were minimal reports of violence despite a massive turnout, one of the largest by percentage of registered voters in Nigerian history.

When the results were released, it became clear that pre-election sentiments were right on the money. MKO had secured a resounding, overwhelming victory over Tofa, even defeating the latter in his home state.

With 8.3 million votes and 53.6% of the total vote count as against Tofa’s 5.9 million votes, MKO was declared the winner of the election.

There was dancing in the streets.

But then things began to go very very wrong.

No-one can settle on the specific reason why this happened.

The day Democracy died

Many believe that Babangida had promised Abacha the seat of power in exchange for the army’s support in months around their 1985 coup and with the clock winding down, the ruthless Chief of Defence Staff had come calling for his end of the bargain to be fulfilled.

Others speculate that the Northern elite was reluctant to see power shift from the North, under such optimistic circumstances.

Since independence, federal power had been held, for the most part, by Northern officers and politicians. With a Southern Muslim introducing the dawn of democracy and civilian rule, the existing power structure was threatened.

Even still, there is a belief that the soldiers were reluctant to hand over power to a civilian who they saw as one of them. Abiola was a friend of the military’s most promising and influential stalwarts.

There are rumours that he had sponsored coups in the past and with their tacit help, had been manoeuvring his way to the presidency over the years.

It is likely that the soldiers saw this as Abiola protecting his altruistic image on the outside, even though he was basically one of them.

Either way, Babangida proved hesitant to announce Abiola as the winner of the elections.

After massive pressure, he seemed ready to do so, but a few weeks after the results were announced, IBB annulled the June 12 elections.

In a message broadcast to the country, Babangida claimed that the process had been incredibly flawed.

“I, therefore, wish, on behalf of myself and members of the National Defence and Security Council and indeed of my entire administration, to feel with my fellow countrymen and women for the cancellation of the election. It was a rather disappointing experience in the course of carrying through the last election of the transition to civil rule programme”.

The nation was thrown into disarray.

Violence erupted in many cities, especially Lagos. Followers of Abiola called for the presumed winner to claim his mandate and stick the people’s voice in the military’s face.

In a speech to the country, Abiola read his intent to millions of Nigerians who were anxious to know what would come of the power tussle.

“It is inconceivable that a few people in government should claim to know so much better about politics and government than the 14 million Nigerians who actually went to the polls on June 12."

“The people of Nigeria have spoken. They have loudly and firmly proclaimed their preference for democracy. They have chosen me as their president for the next four years. They have determined that August 27, 1993, shall be the terminal date of military dictatorship in Nigeria.”

“On that date, the people of Nigeria, through their democratic decision of June 12, 1993, expect me to assume the reins of government.”

"I fully intend to keep that date with history.", he said.

Some victories must be had, however late

The events that followed are some of the most storied in Nigerian history.

By the end of the year, Abiola was languishing in prison, where he would pass away on July 7, 1998.

Sani Abacha would take power from Babangida, after the latter all but fled, to his residence in Minna.

Today, Nigeria is in the 9th year of the longest democratic dispensation in its history, called the fourth republic.

That it has taken 22 years and three heads of state to acknowlege a date that ultimately led to the birth of this democratic dispensation is some evidence of the sentiments that still remain concerning MKO and his mandate.

On the other hand, awarding the tiltle of GCFR to Abiola reeks of a gift that came too late, an acknowledgement that should be too cold to stir any form of appreciation.

It is why many are asking if President Buhari's move is not entirely political, a ploy to elicit support from the South-West by acknowledging one of its greatest sons.

It could well be. The announcement is a little too close to the elections for comfort.

Yet, the political undertones of such a move should not distract us from the fact that the Nigerian government, and in a way, the political elite has finally acknowledged what was, in retrospect, a grave miss and the legacy of a man who Nigerians of those years chose to lead them into a new age.

It is important that some victories are had, however late they may come.

No comments:

Post a Comment